Note : originally written for Sangeet ke sitare group

by – surajit bose

———————————————————————————

Unquestionable talent, chequered career, largely relegated to oblivion, but a final masterstroke to attain immortality.

———————————————————————————

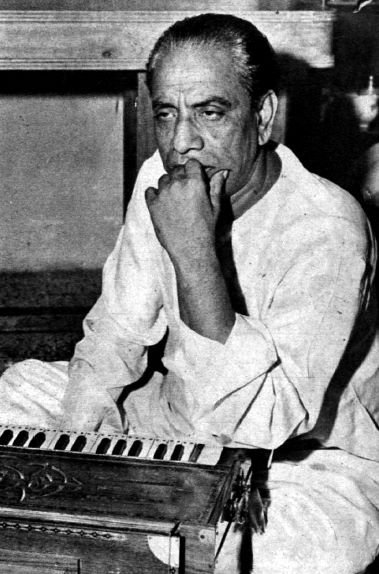

GHULAM MOHAMMED .

Pic courtesy :Kaustubh Pingle

The twentieth annual Filmfare Awards ceremony was held in 1973 to celebrate the cinematic achievements of the previous year. It seemed that Sohanlal Kanwar’s Be-Imaan could do no wrong, racking up seven awards for everything from Best Film to Best Lyrics to Best Male Playback Singer. When Pran was chosen as the winner for Best Male Supporting Actor, however, he turned the trophy down. His reason? He felt that the Best Music Award given to Shankar-Jaikishan for this movie was undeserved; he felt that the honor rightly belonged to Ghulam Mohammed for the posthumously released Pakeezah.

The songs of Pakeezah were, and remain, tremendously popular. Their effortless charm belies the struggle it took to get the movie to screen. Begun in the late fifties, Pakeezah was fourteen years in the making. It was finally completed in 1971, by which time both its cinematographer Josef Wirsching and its composer Ghulam Mohammed were dead. The movie was released in February 1972 and showed every sign of becoming an expensive flop. However, with superbly calculated timing, the heroine Meena Kumari died too, within a few weeks of the release date. Audiences turned out in droves to mourn Hindi filmdom’s most celebrated tragedienne, and the movie became a colossal hit.

Ghulam Mohammed’s superb compositions played no small part in the eventual success of Pakeezah. The central figure of the story was a courtesan, which made the song and dance sequences critical to the story. The most popular song, “inhii.n logo.n ne”, adapted a jaunty tune that had been in prior circulation amongst dancing girls, and had already been used in a couple of earlier movies. Almost equally well-liked were the yearning “chalate chalate yuu.Nhii koii mil gayaa thaa” and the kathak piece choreographed by Lachchhu Maharaj, “Thaa.De rahiyo o baa.Nke yaar re.” These and other songs from the movie are now so firmly a part of the film music canon, it is hard to remember the sensation they created when the movie was first released. So immensely successful were Ghulam Mohammed’s compositions that a few years later, the record company HMV took the unprecedented step of releasing an album of nine outtakes that had been composed for the movie but not included on the soundtrack.

The paradoxes of Pakeezah embody those of Ghulam Mohammed’s career. Like the movie, his career was a quest for perfection beset by difficulties. Like the movie, he seemed destined for oblivion, only to be rescued at the last minute. Pran was prescient: Pakeezah and its music continue to be widely remembered today, while Be-Imaan is justly forgotten. But Pran’s gesture of turning down the award was, after all, purely nominal. It was not going to make the judges change their minds. Similarly, as far as Ghulam Mohammed was concerned, Pakeezah’s success was futile–it came too late to do him any practical good.

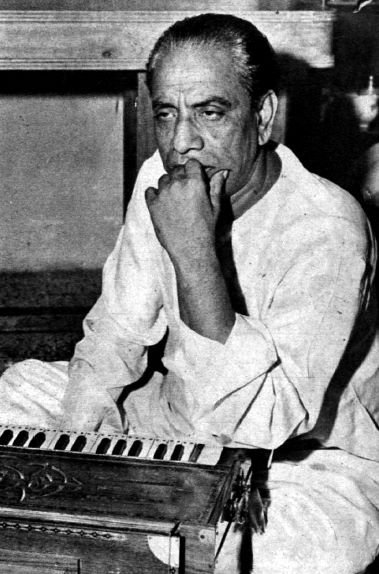

pic courtesy : hamara forums

Ghulam Mohammed was born in 1903. His father Nabi Baksh was a tabla player in Bikaner. Since music was the family vocation, Ghulam Mohammed naturally received training in classical music. Under his father’s tutelage, he became well versed in genres such as Khayal and Thumri, and developed expertise on the tabla. He was also drawn to the folk music of Rajasthan and became adept at the Dholak. Such a dual influence of classical and folk was common among music directors in the 1940s and 1950s; the blend of the two gives the music of that era its distinctive sound. Ghulam Mohammed’s childhood and early training thus provided an excellent foundation for his later career.

As a teenager, Ghulam Mohammed used to join Nabi Baksh in performances at the Albert Theatre in Bikaner. He eventually signed on as a contract artiste for 25 rupees a month, but before he could take up the appointment, the theatre closed due to financial difficulties. He then began work as a jobbing musician, taking whatever appointments he could get in traveling troupes. It is said that on one such assignment, he made it to the princely state of Junagadh, where a minister was impressed enough by his performance to present him a gilded sword.

In 1924, Ghulam Mohammed arrived in Bombay. Regular work eluded him for several years. The emergence of sound in cinema finally afforded him an opportunity. He was engaged as a tabla player at Saroj Movietone for the movie Bhartruhari (1932), whose music composers were Sundar Das and Damodar Das. The movie proved popular, and Ghulam Mohammed received acclaim for his skills as a percussionist. He continued to work as a tabla and Dholak player throughout his career. One commonly heard story is that when Shankar-Jaikishan were composing their maiden venture Barsaat (1949), they insisted on having Ghulam Mohammed play the Dholak for “barasaat me.n ham se mile tum sajan”.

Ghulam Mohammed got his break as an independent music director with Baanke Sipahi (1937). Neither the movie nor recordings of its nine songs appear to be available; it is possible that no recordings were made. Ghulam Mohammed may or may not have actively sought additional work as a music director after this movie’s release. If he did, his efforts were unsuccessful. His next assignment as a composer was not until 1943, for the film Mera Khwab. At least some songs were released on 78 RPM records, such as the sweet female solo “u.D jaa re, u.D jaa papiihe, pii pii mat bol”.

In the meantime, Ghulam Mohammed had had struck up a friendship with Naushad Ali, who had arrived in Bombay in the late 1930s. Naushad faced some initial difficulties, but after the early 1940s, the younger composer began to achieve success. His career soon outstripped that of Ghulam Mohammed. Despite being some 16 years older than Naushad and some five years the senior as a film musician, Ghulam Mohammed began working as his assistant. His collaboration with Naushad spanned ten years and 23 movies, from Sanjog (1943) to Aan (1952).

Beginning in 1947, Ghulam Mohammed’s own profile as a composer began to grow as well. From 1948 to 1955, he composed an average of three films a year. The quality of his output is uniformly high, but some highlights may be recognized:

– a plangent duet from Shair (1949), “yah duniyaa hai, yahaa.N dil kaa lagaanaa kisako aataa hai”, which is both one of the earliest Mukesh-Lata duets and one of the few Mukesh songs to be picturized on Dev Anand

– Cuckoo’s lively dance number from “Pardes” (1950), “mere ghuu.Nghar waale baal”, sung with verve by Shamshad Begum

– the irresistible Rafi-Lata duet from Amber (1952), “ham tum yah bahaar, dekho ra.ng laayaa pyaar, barasaat ke mahiine me.n”, surely one of the most charming confections of Hindi film music

– the song that arguably best showcased Talat Mehmood as a singing star, “zindagii denewaale sun”, a masterpiece of heartbreak from Dil-E-Nadaan (1953).

Ghulam Mohammed’s compositions for Mirza Ghalib (1954) were pathbreaking, and have left an enduring legacy. Prior to this movie, Ghazals were not commonplace in films. Traditionally, they were appreciated primarily as poetry and only secondarily as music. Their somewhat highbrow content was perhaps antithetical to the simpler demands of song lyrics. Today, however, we tend to think of Ghazal as a musical genre first, a verse form second. Indeed, for casual listeners, the musical component of Ghazal has far overshadowed its metrical definition: any soft, romantic, vaguely Urdu-sounding song, irrespective of verse form and meter, is called a Ghazal. Blogs are full of lists of “top ten film Ghazals”, invariably including such non-starters as “zindagii bhar nahii.n bhuulegii” from Barsaat Ki Raat (1960), “mere mahabuub tujhe merii muhabbat kii qasam” from Mere Mehboob (1963), “ra.ng aur nuur kii baaraat kise pesh karuu.N” from Ghazal (1964), etc. It is ironic that Ghulam Mohammed succeeded in making Ghalib wildly popular only at the expense of an accurate understanding of the very genre of Ghazal.

The law of unintended consequences notwithstanding, the songs of Mirza Ghalib richly deserve their reputation. Talat Mahmood and Suraiya do full justice to both the beauty of Ghalib’s poetry and the richness of Ghulam Mohammed’s music. Such Ghazals as “dil-e-naadaa.N tujhe huaa kyaa hai”, “aah ko chaahiye ik umr asar hone tak”, and “phir mujhe deeda-e-tar yaad aayaa” have been set to new music and sung by celebrated Ghazal exponents innumerable times since, but the popularity and accessibility of Ghulam Mohammed’s compositions remains unrivaled.

Surprisingly, the acclaim Mirza Ghalib received did not give Ghulam Mohammed’s career a fillip. His assignments began drying up soon after. He did not go beyond his usual three-movie average in 1955, and had no films at all in 1956. A few one-off assignments dribbled in over subsequent years, spaced out as widely as his earliest movies. The last two of his films released during his lifetime were Shama (1961) and the Bhojpuri Saiyan Se Neha Lagaibe (1965). His straitened circumstances led him to move to Borivili, then a remote suburb at the outermost reaches of the city. His constant companion at the time was Jamal Sen, a fellow Rajasthani who too had never achieved the sort of recognition he might have expected from the excellence of his compositions. Ghulam Mohammed died of a heart ailment on 17 March 1968.

A glance over the entirety of Ghulam Mohammed’s work reveals some enduring characteristics. The obvious one based on his background is his deft use of percussion. His rhythms are rarely complex, but the simple base is deftly overlaid with syncopated patterns that perk up the melody. Take for example the Geeta Dutt – G M Durrani duet for Dil Ki Basti (1949), “naazuk dil hai, to.D na dena”, with its emphatic upbeat of the Dholak on the second beat of the taal. Another way Ghulam Mohammed added spirit to his rhythms was through the use of the maT_kaa, or clay pot. He and Shyam Sundar were the pioneers in its use as a percussion instrument in film music. The solo by Shamshad Begum from Doli (1947), “a.nganaa bole kaag re, uja.Daa man kaa baaG re”, shows how the maT_kaa imparts a light, attractive feel even to an otherwise sad song.

The Dholak and maT_kaa beats in many Naushad compositions almost certainly owe their presence to Ghulam Mohammed. Lata Mangeshkar has stated in an interview that Naushad’s assistants left their stamp on his compositions, citing as an example “Dhuu.NDho Dhuu.NDho re saajanaa” from Gunga Jumna (1961), which was arranged by Mohammed Shafi. She gives no examples of songs where Ghulam Mohammed assisted Naushad, but the arrangements of Naushad’s compositions throughout the period when he was associated with Ghulam Mohammed are practically indistinguishable from the latter’s own. The maT_kaa in “tuu kahe agar” from Andaz (1949), for example, plays exactly the same pattern as that in “a.nganaa bole kaag re.”

“tuu kahe agar” demonstrates another Ghulam Mohammed characteristic: the use of short, staccato interludes. Between “detii jaa sahaare mujhako” and “mai.n raag huu.N tuu biinaa hai” there is an eight-beat step-like interlude with strings played in unison over clarinets and flutes. The signature sound created by this blend is impossible to miss in Ghulam Mohammed’s own compositions. The breathtaking (or not!) Shamshad – Rafi duet “laa de mohe baalamaa aas_maani chuu.Diyaa.N” from Rail Ka Dibba (1953) punctuates the sthaayi itself with a staccato pattern using this signature sound; the Amirbai Karnataki – Mohammed Rafi duet from Bikhre Moti (1951), “aa.Nsuu thii merii zindagii”, employs it in every interlude.

To point out these similarities between Ghulam Mohammed’s arrangements and those attributed to Naushad is not, however, to claim that Naushad was parasitic on Ghulam Mohammed. There is every reason to believe that their relationship was mutually beneficial. For instance, Naushad composed the music for two of his three home productions–Babul (1950) and Udan Khatola (1955). However, he gave the third, Maalik (1958), to Ghulam Mohammed. Maalik is the latter’s only score from that year, when his career was on the wane. It is reasonable to assume that Naushad was helping his senior and erstwhile assistant by sending work his way, knowing he could count on its excellence. The lyricist of Maalik was Shakeel Badayuni, a fixture for both Naushad and Ghulam Mohammed. Over Ghulam Mohammed’s career, Shakeel collaborated with him for 22 out of 37 movies.

And, of course, when Ghulam Mohammed passed away before putting the finishing touches on the much-delayed Pakeezah, Naushad stepped in to compose the background music, re-record one song (“chalo diladaar chalo”), and integrate the others into the final product. The transition between Ghulam Mohammed’s work for the movie and Naushad’s is relatively, though not entirely, seamless. Naushad’s willingness to complete Ghulam Mohammed’s work shows that he thought of the latter as more than just a mere assistant. They were colleagues and friends, and each relied on the other.

Commonalities aside, there are differences, too, between Naushad’s sensibility and Ghulam Mohammed’s. A notable one is in their use of ragas. In quite a few songs, Ghulam Mohammed achieves the rare feat of being both entirely within the grammar of a raga, and unobtrusive about it. He has a far lighter touch than Naushad, who could never compose a raga-based song without underlining the fact. The deftness with which Ghulam Mohammed handles, say, Brindavani Sarang in “muhabbat kii dhun beqaraaro.n se puuchho” from Dil-E-Nadaan, or Yaman Kalyan in “nuktachii.n hai Gham-e-dil” from Mirza Ghalib, is admirable.

Another characteristic of Ghulam Mohammed’s work is the wide variety of singers he used. G M Durrani, Shamshad Begum, Talat Mehmood, Sudha Malhotra, Geeta Dutt, Suman Kalyanpur, Jagjit Kaur, Zohrabai Ambalewali, Sitara, Amirbai Karnataki, Asha Bhosle, and Mahendra Kapoor, among others, all had memorable songs under his baton, in addition to the inevitable Lata and Rafi. This variety was partly a function of his active years. The spectrum of voices seemed to narrow considerably in the 1960s, with singers other than Lata and Rafi increasingly relegated to niches. Since Ghulam Mohammed had effectively stopped composing by then, it is hard to say whether he too would have restricted himself to two or three top names.

One index of Ghulam Mohammed’s creativity is the melodic variety within his songs. Given the brevity of a film song, it is quite usual for every antaraa to have the same tune. But this base case is extremely unusual for Ghulam Mohammed. His songs rarely have a repeated melody throughout. If there are three antaraas, one of them is usually different from the other two; occasionally, all three are different from each other. “dha.Dakate dil kii tamanna ho” from Shama (1961) has three antaraas with two tunes among them; Pakeezah’s “mausam hai aashiqaanaa” has four antaraas with three different tunes among them.

One index of Ghulam Mohammed’s creativity is the melodic variety within his songs. Given the brevity of a film song, it is quite usual for every antaraa to have the same tune. But this base case is extremely unusual for Ghulam Mohammed. His songs rarely have a repeated melody throughout. If there are three antaraas, one of them is usually different from the other two; occasionally, all three are different from each other. “dha.Dakate dil kii tamanna ho” from Shama (1961) has three antaraas with two tunes among them; Pakeezah’s “mausam hai aashiqaanaa” has four antaraas with three different tunes among them.

Ghulam Mohammed’s late scores–beginning with Maalik, with its memorable Talat solo, “zindagii kii qasam, ho chuke unake ham”; through Shama, with its Suman songs such as “dil Gham se jal rahaa hai jale”, in addition to the Suraiya numbers; and, ending, of course, with Pakeezah–show a heightening of this creativity. This is especially notable in the instrumental passages. His range seems broader, his sound less uniform. His orchestration is richer, incorporating guitars, sitars, and other instruments not often heard in his earlier scores. The polish and attention to detail, however, are every bit as much in evidence. These movies contain some of Ghulam Mohammed’s most beloved songs, which makes the decline in the number of his composing assignments from 1956 on a mystery.

It is hard to guess why a composer whose experience with film music dated back to its earliest days, whose perfectionism and sophistication were unflagging, who was by all accounts well liked by singers and colleagues, and many of whose songs were huge hits in his own lifetime, should have languished in such obscurity for the bulk of his career. Nalin Shah provides an explanation of sorts when he ascribes to Ghulam Mohammed a “lack of business sense”, and says that he “was too engrossed in his creativity to worry about his own future”. But perhaps we listeners are the richer for his poverty. By not chasing routine assignments, perhaps Ghulam Mohammed chose to concentrate on perfecting the few songs that came his way; perhaps he ensured his future and ours by bequeathing us a scattered handful of pearls instead of a storehouse of base metals.

Filmography: 37 films

1. Baanke Sipahi (1937)

2. Mera Khwab (1943)

3. Mera Geet (1946)* – with Shankarrao Vyas, Geeta Verma, Bal Mukund, and Reejram

4. Doli (1947)

5. Tiger Queen (1947)

6. Grahasti (1948)

7. Kajal (1948)

8. Parai Aag (1948)

9. Pugree (1948)

10. Dil Ki Basti (1949)

11. Paras (1949)

12. Shair (1949)

13. Rasheed Dulhan (194x)

14. Hanste Ansoo (1950)

15. Maang (1950)

16. Pardes (1950)

17. Bikhre Moti (1951)

18. Nazneen (1951)

19. Ajeeb Ladki (1952)

20. Amber (1952)

21. Sheesha (1952)

22. Dil-E-Nadan (1953)

23. Gauhar (1953)

24. Hazar Raaten (1953)

25. Laila Majnu (1953) – with Sardar Malik

26. Rail Ka Dibba (1953)

27. Guzaara (1954)

28. Mirza Ghalib (1954)

29. Hoor-E-Arab (1955)

30. Kundan (1955)

31. Sitara (1955)

32. Pak Daman (1957)

33. Maalik (1958)

34. Do Gunde (1959)

35. Shama (1961)

36. Saiyan Se Neha Lagaibe (1965) – Bhojpuri

37. Pakeezah (1971) – with Naushad

* In his book “dhuno.n kii yaatraa”, Pankaj Rag mentions that the “Ghulam Miyan” who has composed two songs for Mera Geet (1946) is in fact Ghulam Mohammed.

______________________________________________

Sources:

1. Dissertation by Vidya Arya: “raajasthaan ke vilakShaN sa.ngiit pratibhaa sa.ngiit_kaar shrii khem_cha.nd prakaash”, Rajasthan University, 1992. A few pages of this dissertation touch upon Ghulam Mohammed as being one of three Hindi film composers who formed a “Rajasthan trinity”, the other two being Khemchand Prakash and Jamal Sen. Not always accurate–for example, treats “inhii.n logo.n ne” and “dupaTTa meraa” as two separate songs. Tone somewhat melodramatic and overstated: “filmii duniyaa kii viShailii raaj_niiti ne unhe.n zaar zaar kar Daalaa”. Nevertheless, has some extremely valuable information.

2. Pankaj Rag’s book “dhuno.n kii yaatraa”. Rag mentions that the “Ghulam Miyan” who has composed two songs for Mera Geet (1946) is in fact Ghulam Mohammed. The songs do indeed exhibit the hallmarks of Ghulam Mohammed’s compositions, such as the staccato short instrumental phrases with strings overlaying woodwinds, and the syncopated percussion. The songs are “ham se ruuThe hii bhale” and “tore binaa ho balamaa”, both by Zohrabai Ambalewali.

3. The downmelodylane.com article on Ghulam Mohammed. The essay is a fragmentary and rather poor translation of the relevant few pages of Arya’s dissertation, but the filmography is relatively complete, leaving out only two movies. One is Mera Geet; the other, the Bhojpuri film Saiyan Se Neha Lagaibe (1965). The omission means, of course, that the list given above is the only known complete and accurate filmography of Ghulam Mohammed currently available on the web.

4. Wikipedia entry on Ghulam Mohammed. Consulted but discarded as being nearly entirely worthless. The information is inaccurate and incomplete, the latter being a saving grace considering the former. For example: claims that Ghulam Mohammed won the President’s Award for Mirza Ghalib, when in fact a music director award was not instituted until 1965.

5. Article by Nalin Shah in the Indian Express, 17 April 1999. Posted on the usenet newsgroup rec.music.indian.misc by Kalyan Kolachala on 16 April 1999. Aren’t time zones wonderful?

6. Other postings on rec.music.indian.misc about Ghulam Mohammed. Again, the information there had to be taken with a grain of salt (“yah kaisii ajab daas_taa.N ho ga_ii hai” is neither a Ghulam Mohammed composition, nor from Sikandar-E-Azam, and in any case, the latter movie isn’t one of Ghulam Mohammed’s, nor of Sajjad’s, who really did compose the song in question); but then, as someone who cheerfully promulgated his share of howlers on that forum, I just holler “caveat lector” and have at it.

Acknowledgments:

1. To Aditya Pant and the rest of the SKS deities, first, for asking me to contribute a write-up, and second, for agreeing to my choice of Ghulam Mohammed. I’m honored to be asked and delighted to have had the excuse to explore the work of a composer I’ve always liked without knowing much about. I’m also grateful to Aditya for alerting me to Rag’s book.

I’m honored to be asked and delighted to have had the excuse to explore the work of a composer I’ve always liked without knowing much about. I’m also grateful to Aditya for alerting me to Rag’s book.

2. To my near-namesake Dr Surjit Singh, who sent me a PDF of some pages of Arya’s dissertation, reminded me to check rec.music.indian.misc, supplied me with recordings of Ghulam Mohammed’s earliest compositions, and responded to panicked last-minute queries with customary coolth and aplomb.

3. To all the nettors who contributed posts about Ghulam Mohammed to rec.music.indian.misc.

Any merit in the article is due entirely, etc., and any errors or infelicities that remain are of course, and so on

#Ghulam Mohammed # Ghulam Mohammed composer #composer # music director Ghulam Mohammed